EL ROSARIO, Honduras — On a late winter evening, the people of this remote village walked out of their tin-roofed houses and headed to the local health clinic, a small, brightly painted building that has become a lifeline and a community gathering place.

Worry crossed their faces as they crammed onto wooden benches outside the clinic, shuffling dust-covered cowboy boots and plastic sandals.

They had come with questions.

Last year, farmers here watched helplessly as drought withered their corn and bean crops for a fifth straight year. With nothing to sell and no food supplies to feed their families, they’ve entered this growing season without any reserves.

El Rosario is on the edge of hunger.

As the sun slid below the distant tree line, Nelson Mejia, a big, soft-spoken man in his fifties, stood before his neighbors and prepared to share words of advice. He has been farming in El Rosario almost all his life, and he knows that unless something changes soon, the village could starve — or its 500 residents could be forced to find a new home.

For those who might want to leave — and can afford to — the choices are few. San Pedro Sula, a city a few hours to the northwest, is overrun by drug gangs and violence. Migrant caravans leave from there to the Mexico-U.S. border but offer no guarantee — and hiring a smuggler costs thousands of dollars.

“We know we have to find options,” Mejia said in Spanish through a translator.

Some people here know about climate change, about the vast, complex forces of cambio climatico roiling the weather. Global warming has heated the air and driven away seasonal rains. It may have boosted the spread of bark-munching beetles, which ravaged pine forests surrounding El Rosario that had already been depleted by logging. The loss of the forests, in turn, diminished freshwater streams and sent temperatures in the village soaring still higher, residents say.

Migration to the United States from Honduras and its neighboring “northern triangle” countries — El Salvador and Guatemala — has climbed in recent years. The reasons are complex, including poverty, unemployment and violence. But the increase in migration also coincides with the drought, which began in 2014, and those living in Central America’s so-called dry corridor, which is adjacent to El Rosario, say lack of food is the primary reason people leave, according to a United Nations report.

Last summer, the Honduran government declared an emergency because of food shortages, joining governments in El Salvador and Guatemala, which issued similar alerts. Almost 100,000 families in Honduras and 2 million people across the region lacked adequate food. Making matters worse, a pathogen that scientists believe is worsened by climate change has ravaged the country’s coffee plantations, which means that migrant farm laborers who count on the coffee harvest for income can’t find work.

Researchers and international aid workers say that for Honduran family farmers, like those in El Rosario, to survive, they need support to adjust to the climate’s rapid changes, including instruction in planting drought-resistant crops and help conserving water.

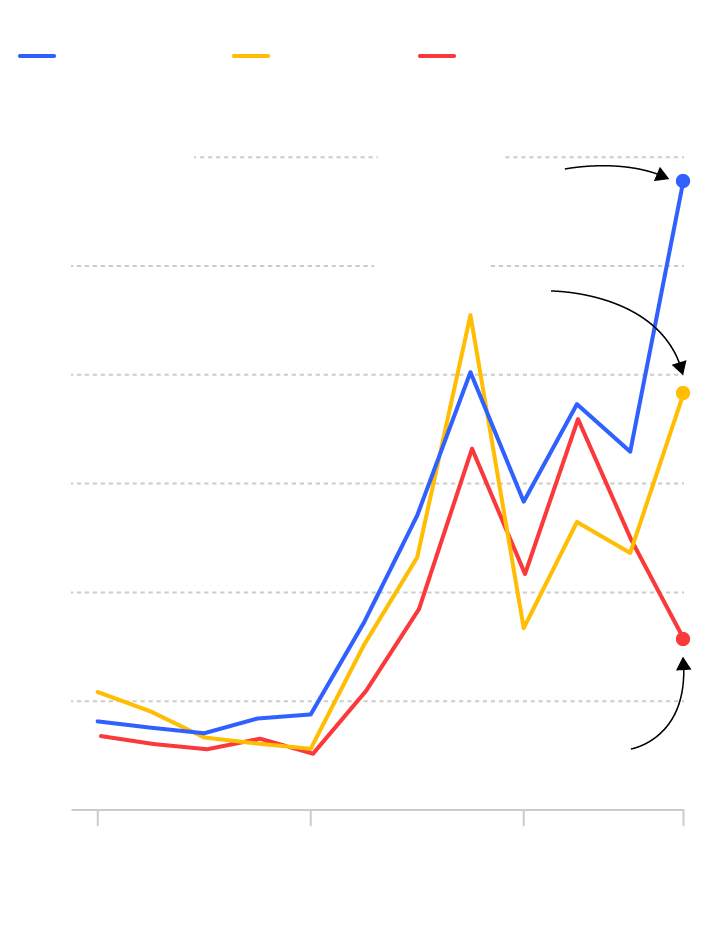

Figures are based on the citizenship of those apprehended by Border Patrol and considered deportable.

Source: U.S. Border Patrol

Graphic: Robin Muccari / NBC News; Paul Horn / InsideClimate News

But Honduras is one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere — almost two-thirds of its population lives in poverty — and its rural, family farmers often don’t have the resources to test out new farming techniques.

The U.S. sends hundreds of millions of dollars in aid to Central America every year, but most of it gets directed to security, drug control or violence prevention programs, rather than agricultural or environmental support. Under the Obama administration, Congress doubled the funding to the region from $338 million in 2014 to $754 million in 2016 and began directing more funding to climate and agriculture programs. The Trump administration has tried to cut funding dramatically — proposals Congress has rejected. Under the current budget, almost $530 million is directed toward Central America.

In March, President Donald Trump said his administration would cut aid to Central American countries to punish them for failing to stop migration flows. The administration made the cuts official in June, saying it would withhold some of the funds allocated by Congress for 2017 and would suspend all funds Congress approved for 2018. Critics have said this will only stoke more migration.

As farmers battle the droughts that scientist have projected will continue, food supplies could dwindle further, shaking security both within and beyond Honduras, with consequences that could reach the U.S. border, experts warn.

“National security rests on economics as well as anything,” said Richard Holwill, who was the deputy assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs in the 1980s. “We can’t just pull up a drawbridge, wall out the rest of the world and say, hey, we can survive here in this island that we call the United States. We are interconnected, and our security is enhanced by ensuring that their world is stable.”

A climate ‘hot spot’

Like many poor, developing countries, Honduras has contributed relatively little to the greenhouse gas emissions heating the planet. Yet it is one of the places most vulnerable to climate change’s effects, according to the U.S. Agency for International Development.

From 1998 to 2017, Honduras was among the three most weather-battered countries in the world, largely because of the devastation wrought by Hurricane Mitch in 1998.

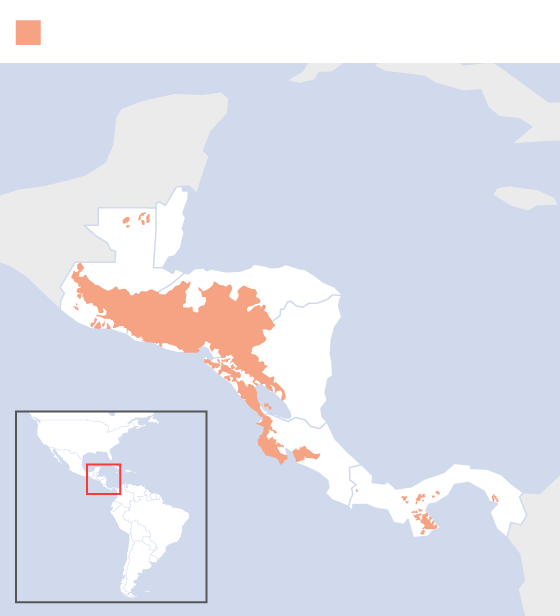

The “dry corridor,” which stretches from southern Mexico to Panama and includes about half of Honduras, has seen some years with up to 40 percent less rain than normal, interspersed with years of heavy rainfall that washes out crops. Western Honduras is predicted to become a climate “hot spot,” or an area that sees relatively more intense effects of climate change, with greater temperature increases than the rest of Central America. These shifts could challenge the Honduran agriculture industry, which employs almost one-third of the population.

Graphic: Robin Muccari / NBC News; Paul Horn / InsideClimate News

Climate change, when layered onto a mix of economic instability, violence and weak governance, can become fuel — a threat multiplier that could aggravate Honduras’ vulnerabilities, leaving people little choice but to flee. Already, immigration analysts note that roughly half the adults apprehended at the U.S. border work in agriculture, underscoring the precarious nature of their lives at home. The World Bank projects that almost 4 million people from Central America and Mexico could become climate migrants by 2050.

Some parts of the world have already experienced this kind of combustion. Researchers argue that drought in Syria droveinternal migration that contributed to instability and, ultimately, the civil war that killed hundreds of thousands of people and forced millions from their homes.

While the links among climate change, migration and security are complex, researchers believe this type of chain reaction could become more common.

“The physical impacts of climate change are set to become the fastest-growing driver of involuntary migration and displacement globally, beginning in the middle of this century,” Robert McLeman, a Canadian researcher, wrote in a 2017 report. “States that are already politically fragile are the most likely future epicenters for climate-related violence and forced migration events.”

‘There is nothing’

In neighboring Guatemala, more and more families are making the choice to leave their homes — the same choice the people of El Rosario are worried they may have to make if things get worse. Guatemala, like Honduras, has faced years of drought that scientists believe is driven by climate change, straining rural farmers who live on the corn and beans they grow.

Juan de León Gutiérrez grew up in Tizamarte, a small village in southeastern Guatemala, in the dry corridor, where he watched as the drought decimated his parents’ corn and bean crop. In early April, Juan, 16, decided to set out for the U.S. border in the hopes of getting a job and sending money home.

Less than a month later, he was dead. After crossing into the U.S., he fell ill while being held at a children’s detention facility in Texas, and died of complications from an infection. He’s one of five children from Guatemala to die in U.S. custody since December.

Juan’s parents described him as helpful with carrying water and gathering firewood, proud that he had grown as tall as his mother and eager to continue attending school, which the family could not afford. Juan spoke frequently about going to the U.S., following hundreds of others from the El Tesoro region who had left. He planned to stay in the U.S. for no more than three years before returning home. Though his parents were reluctant, they ultimately gave him their blessing.

“But I didn’t know how he was going to come back,” Tránsito Gutiérrez, Juan’s mother, said in Spanish from the family’s home, a mud cottage without electricity overlooking the surrounding mountains.

“He came back in a coffin,” Tanerjo de León, Juan’s father, said.

Tizamarte was once a place where growing corn and beans could feed a family, where the central bodega was such a busy meeting point that the owners had to add a second window.

Then came the drought, which began several years ago. Rain that was once regular is now unpredictable, drying out the crops before they have the chance to develop. Occasional deluges make things worse, washing the soil from the steep, rocky hillsides. The bodega’s shelves are nearly empty, and almost no one stops by.

“It’s fewer days of rainfall but more intense rainfall, sometimes harmful because it’s so strong,” said Alex Guerra Noriega, general director of the Climate Change Research Institute in Guatemala. “And then you get a few weeks with no rainfall and then you have these drought conditions and your crop fails.”

There are 1 million families living on subsistence farming in Central America’s dry corridor, Noriega said, and there are no public assistance programs available to those in the poorest, most remote areas such as Tizamarte.

“There is no money,” Gutiérrez said. “Today, if people don’t go far to earn money, they starve.” She sees her son’s death as the result of the changing climate and the lack of food. “They say he died of an illness,” she said. “He didn’t die of an illness — he died of need. Because there is nothing.”

‘The land never rests’

The road into El Rosario in north-central Honduras, about 170 miles north of the capital Tegucigalpa, climbs through the scrubby hillsides for several miles, then slopes downward as it approaches the village primary school and a library with a hand-painted wooden sign above the threshold: “La Biblioteca Regional de Dr. Dean J. Seibert.”

Seibert, 86, is a doctor from Vermont who taught at Dartmouth College’s medical school for decades and a veteran of humanitarian emergencies. He has worked in Liberia, the Balkans, Indonesia and Pakistan, and he first came to Honduras two decades ago after Mitch decimated the country, burying villages in landslides and killing thousands.

He now runs a small community development organization called ACTS, which is based in Vermont and has worked in El Rosario for 30 years. ACTS initially focused on growing and improving medical facilities and schools in the area, but several years ago, as the drought worsened, Seibert shifted the organization’s work to a more urgent need: ensuring the people of El Rosario can grow their own food.

He sought out agricultural experts and is trying to organize a local committee to tackle the problem — to find new varieties of drought-resistant crops, new ways of irrigating, new ways of treating the soil so it’s more resilient.

“Things have changed, and we’re really not geared for that,” he said.

During Seibert’s most recent visit to Honduras, in February, a handful of El Rosario residents, including Nelson Mejia, traveled to the Honduran Agricultural Research Foundation near San Pedro Sula. They listened as the foundation’s experts offered ideas on how to farm — to survive — in their parched valley.

Mejia described the challenges: lack of water, erosion, poor soil. “The land never rests,” he said.

The foundation, launched in 1984 with money from American fruit companies and USAID, is sprawled across an old plantation that once housed a swanky club for the bigwigs of Big Fruit — the industry that turned Honduras into the original “banana republic” in the late 1800s. The legacy of those companies remains. Critics say they took the best Honduran farmland, pushing farmers into the hills, to places like El Rosario where the soil is poor, sloped and difficult to farm.

Victor Gonzales, the organization’s head of research, suggested the farmers plant crops that do not require much water, such as sorghum, and those with deep roots, to control erosion. Gonzales also advised the farmers to rotate crops to allow the soil to recover from the continuous planting of corn and beans and to create drainage canals to contain water when it rains. He showed them a “water box” — a moat of sorts — that catches rainwater at the base of trees.

Gonzales said he understood that farmers in the region may be skeptical of trying anything new. “When you have nothing, risk aversion is very high,” he said.

Mejia listened carefully and took notes. It would be his job to tell his neighbors what the group had learned when he returned to El Rosario.

A difficult change

Two days later, Mejia stood before his fellow farmers as the sun set outside the health clinic. He knew that some of them would need convincing.

He told them about new cash crops such as avocados and plantains, and about crops that can survive in the heat with less water. He described grasses that hold the soil in place and trees that create windbreaks. He said they could do a better job channeling and holding onto the little rain they’d been getting.

But without more financial help and technical advice, making these switches will prove difficult. El Rosario is so isolated, and farmers are so accustomed to doing things the way they have for decades, that making any major shifts to account for the changing climate will take time. Little foreign aid is focused on agriculture, especially small-scale subsistence farming.

After Mejia concluded, the crowd got up and gathered in clusters, chatting and mulling what they’d heard. Bony horses and cattle wandered by. Chickens pecked at the dirt. Their owners started rationing food a couple years ago.

Soon everyone left to make it home in time for the last of the running water, which is turned off in the evenings as a conservation measure.

Dionisio Cabrera, a longtime resident and farmer in his 50s, said new crops and technology are important, but they won’t mean much without reliable rain.

“This community lives because of water,” he said.

Georgina Gustin, InsideClimate News, reported from Honduras. Mariana Henninger, NBC News, reported from Guatemala. Nicholas Kusnetz, InsideClimate News, contributed reporting from New York.