If political instability is throwing off United Nations climate talks now, what will the next few decades look like?

With barely a month’s notice, Chile canceled plans to host the annual United Nations climate summit as fiery protests against austerity and widening inequality engulfed the country for a third week.

Chile’s neighbor, Brazil, had initially been slated to hold the 25th Conference of the Parties, or COP25. But after years as a climate champion, South America’s largest country elected far-right ideologue and climate science denier Jair Bolsonaro as its new leader in November 2018. One of his first moves was to withdraw as host.

Chile’s announcement sent the United Nations scrambling Wednesday to secure a new location for the highly choreographed gathering of the world’s leaders. The debacle also raised an unsettling question: If unrest is already destabilizing middle-income countries, how will the world work together in the decades to come as the effects of climate change worsen?

“It’s a warning,” said Francesco Femia, co-founder of the Washington-based nonprofit Center for Climate and Security. “We’re in trouble from a security perspective, and the window is closing.”

The climate alarms are blaring now. In March, an unusually powerful cyclone destroyed 90% of Mozambique’s second-largest city. In July, scientists at the World Meteorological Organization registered the hottest month in recorded history. In August, the Greenland ice sheet expelled 11 billion tons of melted glacier into the ocean in a single day.

None of these milestones is directly fueling unrest in South America. But as still-surging carbon emissions heat the planet, countries south of the equator face most of the gravest forecasts about the effects of climate change: extreme weather, mass displacement and disrupted supplies of food and water. Those conditions will be highly likely to inflame the existing tensions over inequality and breed distrust in political systems that failed to avert catastrophe.

In Brazil, the contrast between impoverished favelas and so-called “Brazilianaires,” coupled with a harsh economic downturn, set the stage for Bolsonaro. Then he surged in the polls after the leading presidential candidate, popular former leftist president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, was jailed on a politically driven corruption conviction.

In Chile, a 4% fare hike to ride the capital city’s metro ignited a populist protest that, as Vox reported, many failed to predict in a country hailed as one of the region’s most business-friendly. Half of Chilean workers earn less than $550 per month, according to a recent study by the Santiago-based think tank Fundación SOL. The United Nations estimated in 2017 that the richest 1% of the population nets 33% of Chile’s wealth, making it the most unequal member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the 36-nation club of developed economies. Forbes pegs President Sebastián Piñera’s net worth at $2.8 billion.

“The fact that this COP would be held in Latin America and the Caribbean would have given us an excellent opportunity to discuss the challenges the region has in the face of an unfair system that deepens climate change effects while driving profound inequalities,” said Alejandro González, a senior adviser on climate change in Latin America for the British-based relief agency Christian Aid.

“We’re in trouble from a security perspective, and the window is closing.”

-Francesco Femia, co-founder of the Center for Climate and Security

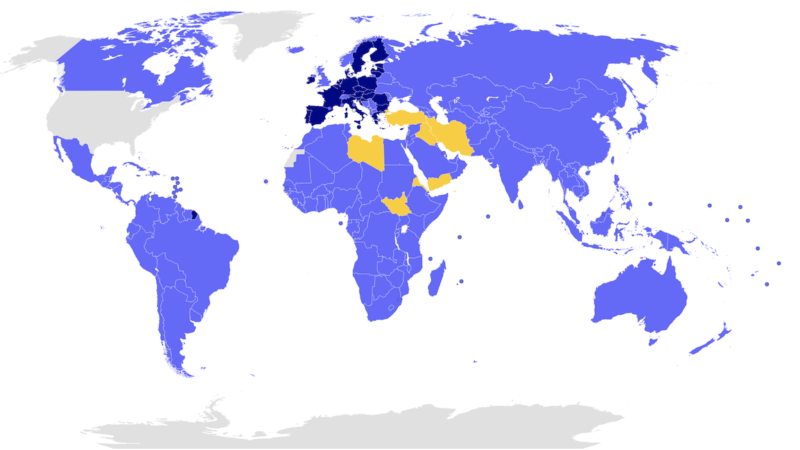

Chile’s decision to cancel underscored the political risks that have always dogged the climate movement. Decades of global talks about whether to recognize the threat of heat-trapping emissions and how to prevent global warming finally reached a breakthrough in 2015, when the United States and China ― the world’s largest emitters ― committed to reduce their carbon dioxide output as part of the Paris agreement.

But the pact was nonbinding, and efforts to create rules to enforce the deal sputtered over the last few years as even enthusiastic signatories failed to make substantive emissions cuts. Things became more complicated when President Donald Trump, who routinely mocks climate science and seeks to boost fossil fuels, announced plans to withdraw the U.S. from the Paris accord. With the world’s largest economy openly flouting the pact’s pledges, poorer countries whose combined emissions could have the biggest impact on warming over the next century had even less incentive to make costly and risky changes. Bolsonaro’s election gave Trump another high-profile ally.

“We need to develop and implement a set of strong global agreements to tackle the threat of climate change that is independent from, and can survive, the short-term vagaries of politics,” said Peter Gleick, a climate scientist and co-founder of California’s Pacific Institute. “[Responding to] climate change is too important to be held hostage to the ebb and flow of national politics. We must put in place a system that can address the long-term threat of climate change.”

Some fear the disruptions yet to come could embolden authoritarian movements and accelerate a retreat from the liberal democratic model that has dominated the developed world since World War II. Even as China’s emissions grew, the country’s investments in renewable energy and electric vehicles made it the unrivaled leader in technologies seen as necessary to cutting emissions. Now, as China expands its influence abroad with a massive global investment program and construction of military bases, the country’s authoritarian model “could be enhanced by the perception that democracies are incapable of dealing with real problems like climate change,” said Femia.

The fact that hosting the next climate summit appears to be a hot potato “feeds into the perception that authoritarian governments are working and democratic governments are not,” he said. “And what better way to make that case than on the biggest crisis we all face?”