Environmental regulations aren’t the reason that coal is falling off the map.

By Karin Kirk

August, 2019

Is environmental extremism causing the decline of the American coal industry? A look at the economics shows that coal has been beaten fair and square in the marketplace by cheaper and cleaner alternatives. The best way to support coal communities is to confront these economic realities, rather than creating a divisive and false narrative about the reasons behind the industry’s challenges.

Talen Energy in June announced the early closure of part of its Montana Colstrip power plant, the sixth-largest source of greenhouse emissions in the U.S. Two of the plant’s four coal-burning units are to be shuttered at the end of this year. The plant, and now its closing, are emblematic of the struggle between the fight to save coal communities and the inevitable economic forces plucking away at coal’s one-time dominance of American energy.

The Colstrip plant has four units, each its own power plant. The two oldest units, Units 1 and 2, are closing in light of insurmountable headwinds. They emit so much pollution that under federal law they are not permitted to operate unless the relatively cleaner units are also running and the net pollution then can be averaged-out. These 43-year-old units are also expensive to run compared to the amount of power they generate, so they are seldom used.

Rising costs are ‘an unfortunate pas de deux, with both parties locked into a downward spiral.’

The power plant is fed by the nearby open-pit Rosebud mine, owned by Westmoreland Coal Company. Westmoreland recently emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy and needs to raise prices in order to keep the Rosebud mine solvent. But increasing the cost of coal tips the economic balance of the power plant still further into the red. It’s an unfortunate pas de deux, with both parties locked into a downward spiral.

This same story is repeating itself elsewhere across the U.S. in a transition that is celebrated by environmental advocates and considered a “war on coal” by President Trump and many elected Republicans. Montana’s Republican Senator, Steve Daines, echoed a familiar refrain in his press release about the Colstrip closure, claiming “yet another example of the devastating impacts of extreme environmental regulations, fringe litigation, and partisan politics.”

Divisive finger-pointing may seem a tempting response, but let’s dig a little deeper. Are environmental regulations and fringe litigation to blame for coal’s downturn? In short, the answer is no. The real answer comes down to simple economics, as illustrated here in six short points.

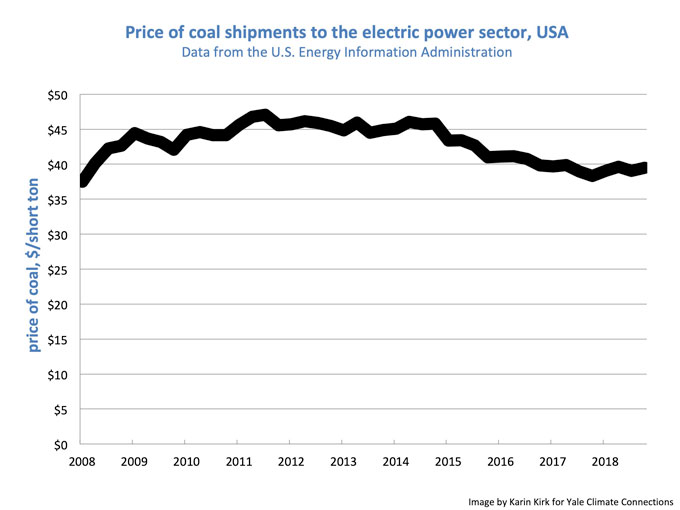

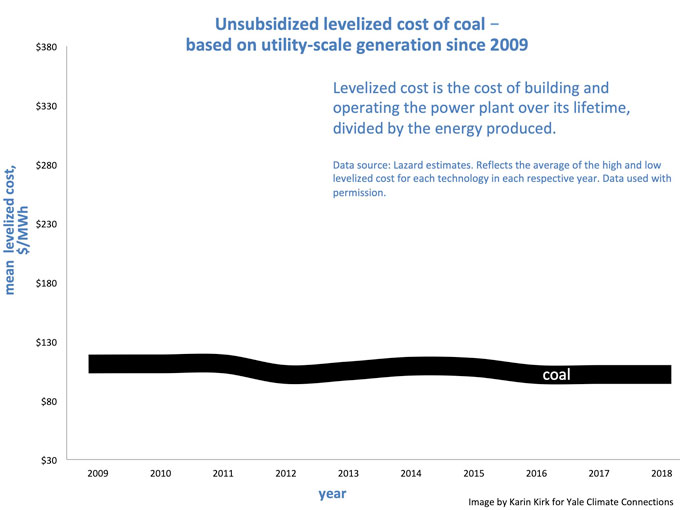

1. The price of coal has not increased.

If “extreme environmental regulations” were putting a burden on coal, one would expect to see coal’s price rising. But the price of coal for the electricity sector has been fairly flat. If anything, coal has gotten cheaper over the past four years.

One might wonder if the cost of raw coal has not changed, but perhaps the price of burning it in a power plant has increased? No, not according to the levelized price of coal-powered electricity, which takes power plant operations and maintenance into account. Again, the cost of coal is stable.

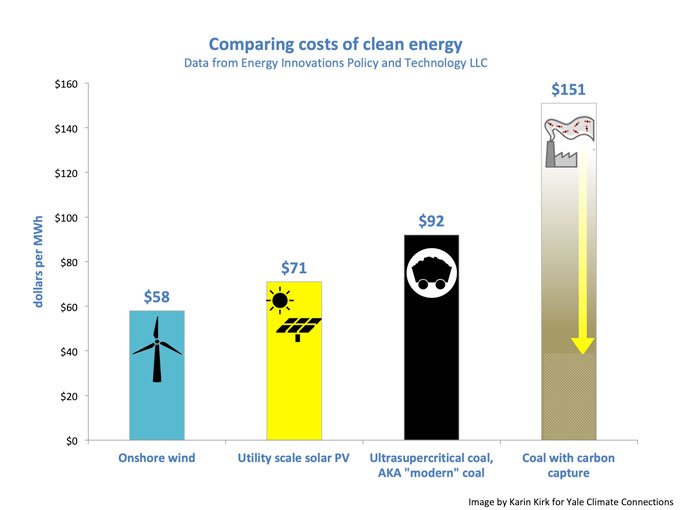

2. The price of coal has been undercut by cheaper, cleaner competitors.

The decline of coal markets has little to do with coal itself. Instead, coal has been upstaged by cheaper alternatives, which enjoy the additional benefit of being cleaner. Natural gas, utility-scale solar, and onshore wind have all dipped well below the price of coal. Such falling energy prices, improving technology, and cleaner air are improvements that would normally be celebrated, but coal industry rhetoric has turned those wins for society into “a war,” and those wins have been lost in the rhetorical shuffle.

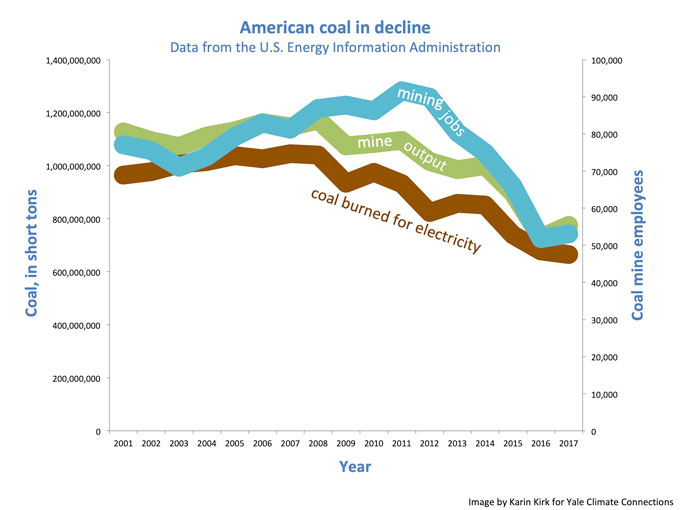

3. Because of these factors, the coal industry is declining in the U.S.

Since 2007, the amount of coal burned for electricity generation has fallen by a whopping 39 percent, and mine output and employment have endured similar declines. A small rebound has occurred since 2016, driven by coal-friendly policies of the Trump administration. But viewed in context of the big picture, as Associated Press has reported, “The outlook for thermal coal, the type used to fire power plants, has been bleak.”

4. Coal bankruptcies hit workers and retirees the hardest.

Since 2015, four of the six top-producing American coal companies have declared bankruptcy, with Revelation Energy the most recent addition to the list. Three have exited bankruptcy by restructuring debt. Peabody Energy emerged from bankruptcy in part by winnowing away coal miners’ retirement benefits by 88%. But those austerity measures appear not to have applied to executive benefits, and Peabody’s bankruptcy settlement included $11.9 million in cash bonuses for top executives.

Colstrip’s Westmoreland Coal Company followed a similar playbook by cutting health benefits and black lung compensation for retired miners as a way to ease $1.4 billion in debt in the company’s third round of bankruptcy. At the same time, Westmoreland issued bonuses for management.

5. Clean coal sounds great, but only exacerbates the high cost of coal.

“Clean coal” has a few different definitions. To some, it’s primarily a rhetorical refrain.

But to truly be clean and environmentally competitive, carbon emissions from coal have to be mitigated, through carbon capture and storage. Only one coal plant with carbon capture, Petra Nova in Texas, has been successfully built in the U.S. A second plant in Kemper County, Mississippi, had been under construction, but cost overruns have forced project managers to change course and the carbon capture components were never completed, despite a $7.5 billion price tag.

Given the complexity and lack of examples of “clean coal,” it’s hard to pin down its price. The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates coal with carbon capture would cost more than twice the price of wind, solar, or gas. Another analysis, from Energy Innovation: Policy and Technology LLC, concluded that coal with carbon capture would have a price tag two to three times higher than the unsubsidized price of wind and solar.

But advanced math isn’t really necessary. Even “dirty” coal can’t compete on price, so adding more costs to coal only tilts the economics further away from coal’s favor. The math shows that it is far cheaper and simpler to use sources of energy that are inherently cleaner in the first place.

6. ‘Affordable Clean Energy’ rule will not save the coal industry.

The Trump administration has made numerous attempts to prop-up the coal industry. Its latest effort, the Affordable Clean Energy rule, scraps the emissions targets proposed by the Obama administration and calls for only modest emissions reductions from coal-powered electricity. The relaxed rules, certain to face court challenges, will allow more coal to be burned, but that can’t alter the fundamental economics that plague the coal industry. Case-in-point, the U.S. Energy Information Administration projects further declines in U.S. coal production in 2020 as a result of “declining coal consumption in the electric power sector and a lower forecast demand for U.S. coal exports.”

In the end, the perceived “war on coal” is primarily a consequence of better, cleaner, cheaper technology – typically the types of innovations that are encouraged rather than thwarted. Given market forces, no amount of industry favors can reverse these developments.

But the closure of mines and power plants presents acute challenges for coal communities, and experts agree that steady leadership is essential to plan ahead and ease the hardship for coal workers and their families. This is precisely why elected officials would do well to look past partisan potshots and focus on the core reasons the industry is changing. Only then can they come to grips with the economics of coal, and navigate toward long-term alternatives, which ultimately, will benefit everyone.